17 May Repair Your Gut, Reverse IBS and other Autoimmune Conditions Via Trauma Recovery

Trauma and The Gut

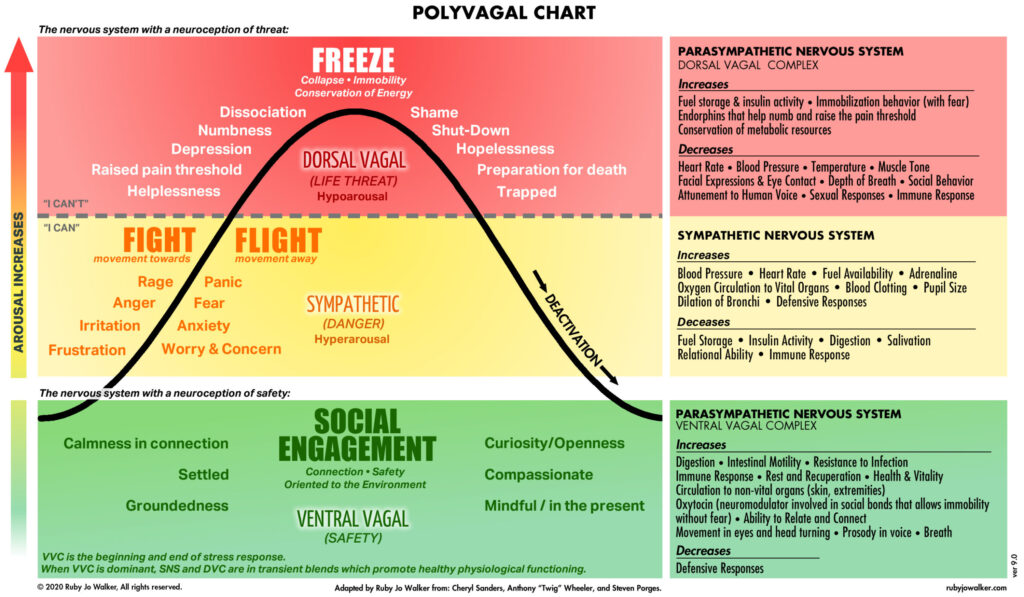

The Polyvagal Theory is the product of decades of research by Dr Stephen Porges and his team at the Brain-Body Center in the University of Illinois, Chicago. Adopted by clinicians around the world, the Polyvagal Theory has provided exciting new insights into the way our autonomic nervous system unconsciously mediates social engagement, trust, and intimacy, and how these may be influenced by our interactions with others.It was whilst studying the evolution of the nervous system that Porges first made an important discovery concerning the vagus nerve which alters the way we understand autonomic nervous system functions. Before this time it was widely understood that our autonomic nervous system operated in a balanced sympathetic/parasympathetic manner, but Porges research changed this through two discoveries; firstly that the vagus nerve in mammals has not one but two branches, and secondly that the newest branch is able to inhibit other nervous system activity. Porges research showed that in the process of evolution, animals first developed immobilised defense responses (innervated by the vagus/parasympathetic system) –where they would adaptively collapse, shut down or feign death when faced with threats. Over time, the nervous system evolved to enable mobilised responses to threat through the activation of a sympathetic nervous system. This mobilised circuitry was able to speed up the heart and lungs, and act on the same visceral organs as the parasympathetic system, in order to promote adaptive fight, flight and active freeze responses to threat. The third stage of evoluntionary development saw the addition of a newer branch of the vagus nerve which is also able to slow the heart and lungs and which links the innervation of these two with the use of facial nerves involved in social engagement. For this reason, Porges theory proposes that this newer Vagal ̳brake‘ evolved in order to make social engagement possible. Without this branch, our hearts would race at around 110 beats per minute. This enables mobilised responses to threat with ease but makes natural conversation very difficult.

The theory proposes that the two branches of the vagus are related to different behavioural strategies, and work in concert with the sympathetic nervous system. One branch – the newer ventral one – is involved in regulating the heart and lungs during social interactions in safe environments (our most evolved system) and the other branch- the older dorsal one – is involved in regulating adaptive physiological states in responses to life threat including mobilised and immobilised responses. Activation of the newer vagus simultaneously calms the viscera and regulates facial muscles, enabling and promoting positive social interactions in safe contexts. This system is an open system, altered by our interactions with others. Transitions between stages in the hierarchical system as we manage and adapt to our environment are described by Porges as neural exercises. The ability to easily transition between stages is important both when we are safe (facilitating play and sexual intimacy) as well as unsafe (enabling adaptive defensive states) and is normatively learnt in the early years of life through our experiences with our primary caregiver. Humans are biologically driven to respond to distress first by social engagement. If we are unsuccessful (our parent, care giver, partner or friend is unresponsive or uninterested) our newer vagus shuts off and mobilisation takes over. If our attempts to defend ourselves through mobilised fight, flight or active freeze responses are also unsuccessful (we are not quick enough, loud enough, strong enough to protect ourselves or engage protection) we drop down the hierarchy again and our dorsal vagus initiates immobilised defence responses, shutting us down and diverting energy to preservation of life on the inside, whilst potentially even feigning death on the outside. The biology behind this model helps us to understand that the use of these responses in children is in fact hierarchical, dependant on the success of more evolved responses. The immobilised (hypoarousal) set of responses can be adaptive, but are less evolved and potentially more dangerous than the mobilised (hyper arousal) responses. Children can develop a kind of ̳hard-wired‘ autonomic nervous system response to trauma and its triggers due to the ongoing need to utilise the circuitry to promote adaptive defence strategies. Over time they decrease their capacity to access their social engagement system (since this has not been used successfully in great amounts), and as more and more of the world is perceived as unsafe, they come to rely on their defensive states to negotiate their environments, making social engagement very difficult. Porges research has revealed that how our nervous system interacts with our environment depends on not just the absence of threat, but the absence of nervous system perceived threat. He has developed the term ̳neuroception‘ to describe our perception of safety not just consciously but also – and often exclusively – at a below cognitive level (Porges 1998, 2001, 2003). It is this neuroception of safety that promotes the ability to utilise our newer system and circuits, whilst conversely, the lack of safety promotes a return to using older circuits to mobilise or immobilise in the face of neuroceived danger. When our nervous system detects safety our system adjusts and makes it possible to enjoy closeness without fear, and keeps us from entering defensive physiological states of mobilised hyper arousal and immobilised hypo arousal, whilst still enable the use of these circuits in safe ways.

The Polyvagal model assumes that for many children with social communication deficits, including those diagnosed with autism, the social engagement system is intact. Yet these children struggle to successfully engage in voluntary social behaviours and engage the newer circuitry due to their nervous systems neuroceiving threats in their environment. Over time these children have lost muscle tone in the face and head also – especially in the middle ears and from the middle of the face upwards around the eyes. To improve spontaneous social behaviour, researchers at the University of Illinois in Chicago working alongside of Porges have reasoned an intervention must stimulate the neural circuits that regulate the muscles of the face and head. Polyvagal Theory predicts that ―once the cortical regulation of the brain-stem structures involved in the social engagement are activated, social behaviour and communication will spontaneously occur as the natural emergent properties of this biological system‖ (Porges, 2004). They have successfully piloted a ̳listening project‘ showing successful outcomes of this hypothesis, giving us a basis from which we now know that neuroception of safety is essential for social engagement, and that neuroception can be altered given the right environments and understanding of nervous system function. It is worth noting that for some individuals – in particular those on the autism spectrum or with complex developmental trauma histories, Porges highlights that social engagement itself is perceived as threatening, and in these cases, clients have an extremely limited capacity to access this circuitry. In these cases, face to face engagement or eye contact will not be appropriate means of initial work since these will trigger stress responses in the child. The circuitry can however be re-accessed by utilising other facial nerves (such as the inner ear muscles and vocal prosody), Music Therapy, as well as Body Therapies promoting breathing and movement. By establishing safety and stabilisation of the ANS responses, we increase the capacity for meaningful relational engagement – thus paving the way for more traditional forms of therapeutic response. And, using the principles of neuroplasticity, these exchanges might then begin the reparation process, compensating for that which has been missed in early childhood. Since engagement is considered essential in all educational settings, and the skills to socially engage are considered essential to success in life, the neuroception of safety becomes an essential starting point in any approach. Being mindful of the child or young person‘s neuroception will have implications on building design, sensory inputs and spaces, models of engagement and therapy and on consultation with families, carers, schools and other places in which our clients/students are regularly involved.

A child‘s (or an adult‘s) nervous system may detect danger or a threat to life when the child enters a new environment or meets a new or strange person – and this is a particularly important consideration for school staff attempting to engage these children, potentially in new environments. In assessing and building environments for the education of these children, this might mean considering things that can activate the brain stem structures involved in the social engagement circuitry. Reducing background noise is an important step. Children who have had little successful use of their social engagement are likely to have little tone in their middle ear muscles which are used to filter out background noise and focus in on human voice. Ordinarily, the switch in ear muscle function happens spontaneously when our nervous systems detect safety and thus allow us to ̳tune in‘ to conversations or the human voice. Sensory stimulation, light and vestibular movement (rocking in a forward-backward manner), or proprioceptive movement, posture and the introduction of calming spaces are further activities that have been shown to promote sensory integration and which influence neuroception of safety (Porges, 2011). One might also need to increase the child or young person‘s sense of control over their environment – considering what sensory options could be offered such as changeable lighting and noise, colour and texture. These are interventions which have been being applied in the field of occupational therapy for some time, which are easily transferred to trauma work. Quick lower cost introductions could include sound deadening tiling, rugs on non-carpeted floors, controllable lighting switches, room adjusted heating and cooling, creation of music of different varieties using the pitch requiring middle ear muscles, availability of head phones to promote safety where necessary, colour, texture and smell options for sensory stimulation. Importantly, Porges theory also reinforces the importance of predictable and consistent adults and caregivers. Familiar caregivers are considered be essential to children‘s neuroception of safety—which, in turn, are essential for the promotion of appropriate social behaviour. Specifically, a child‘s ability to recognize a caregiver‘s face, voice, and movements (the features that define a safe and trustworthy person) should set in motion the process of subduing the limbic system and allowing the social engagement system to function.

The Sociality of The Nervous System

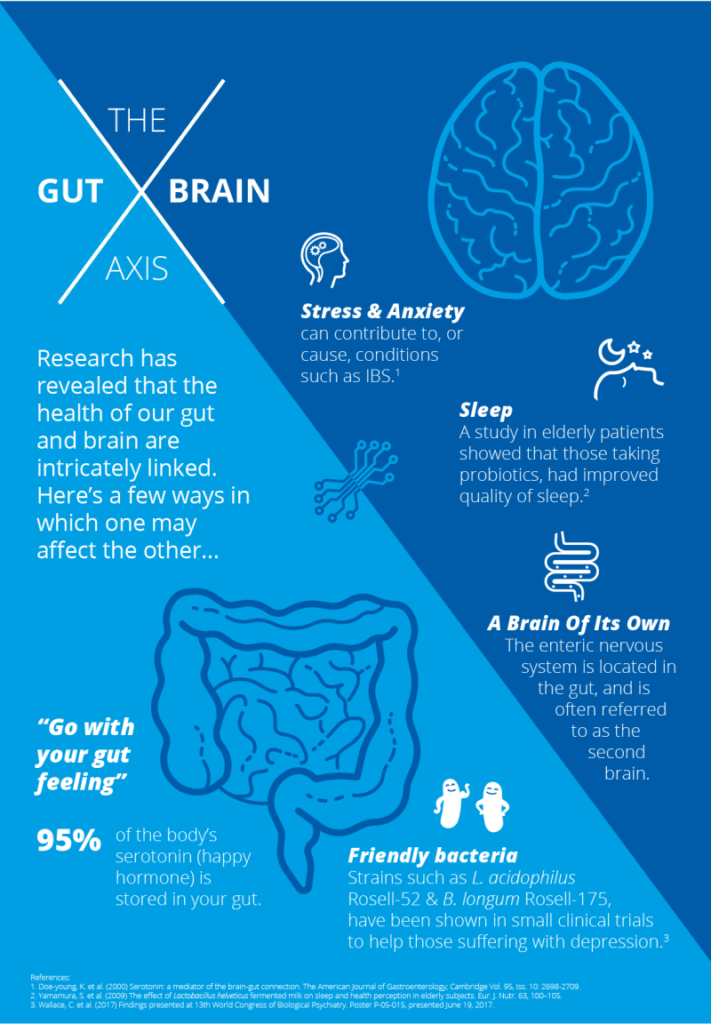

One of the painful repercussions of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is the experience of a lack of control that can occur when you feel trapped by feelings of anxiety, panic, overwhelm, or despair. Polyvagal theory, the work of Stephen Porges, M.D., offers a valuable framework for understanding and effectively responding to the intense emotional and physiological symptoms of PTSD. A basic model of the nervous system shows that we have two components of our nervous system, one that is under our conscious control (e.g. moving your hand) and another that functions without our awareness (e.g. regulating our body temperature). The portion of the nervous system that functions without our conscious awareness is called the autonomic nervous system (ANS). Historically the ANS was understood to have two primary systems: The parasympathetic nervous system which used to be only associated with a relaxation response and The sympathetic nervous system which was historically only thought to be related to fight and flight. More recently, research by Dr. Stephen Porges offered a new understanding of the ANS. The autonomic nervous system is regulated by the vagus nerve or the tenth cranial nerve. The vagus nerve connects the brain to major systems in the body including the stomach and gut, heart, lungs, throat, and facial muscles. Porges identified that the autonomic nervous system does not simply have two systems but a third component that plays a central role in the regulation of the nervous system. His polyvagal theory reveals that our nervous system reflects a developmental progression with three evolutionary stages.The earliest evolutionary set of actions is maintained by what is called the “dorsal vagal complex.” This branch of the vagus nerve engages the parasympathetic nervous system in an unrefined manner, is sometimes referred to as an abrupt vagal brake because of the capacity to engage immobilizing defensive actions such as fainting or feigned death. The second evolutionary stage of nervous system is maintained by the actions of the sympathetic nervous system responsible for actions mobilize us into self-protection when under stress. The most recently evolved portion of the nervous system is the “ventral vagal complex” which Dr. Porges has termed the “social nervous system.” This more recently evolved branch of the vagus nerve also functions as a brake on sympathetic activation; however, this occurs in a highly refined and regulating manner resulting in a calming and soothing effect. Importantly, both the dorsal vagal complex (DVC) an the ventral vagal complex (VVC) will exert inhibition on the sympathetic nervous system only the DVC can have serious repercussions on mental and physical health whereas the VVC is associated with increases in health and emotional wellbeing. Our natural state of rest and safety allows us to engage our social nervous system (VVC) facilitating our ability to connect to others, feel playful, feel love, and relax into connection. When we experience threat we will initially attempt to use our social nervous system to re-establish connection and safety. For example, “tend and befriend” behaviors are a stress response that attempts to re-establish a safe relational bond. However, if our social nervous system fails to resolve stress we will resort to evolutionary older strategies. Initially we will draw upon sympathetic actions such as fight or flight. Again if we are unsuccessful in handling stress at this point we default to the oldest evolutionary survival strategies that are rooted in DVC parasympathetic activity such as immobilization or dissociation. You know that you are engaging the social nervous system when you are able to recognize when you are safe, be self-reflective, feel a warmth in your smile, and the sparkle in your eyes. Your social nervous system increases your ability to respond effectively when you feel keyed up with anxiety or shut-down with depression. Furthermore, your social nervous system (VVC) is strengthened by myelination. Myelination is a fatty coating on nerve pathways that is increased through repeated use and results in increased speed and control. You can imagine here the myelination that occurs in the learning of a new piece of music for the piano. Initially notes are played slowly and carefully but with repeated practice you begin to create music, eventually without reading the music at all. Likewise, the pathways of the social nervous system are strengthened through repeated practice.

Mobilization into Play – Immobilization into Intimacy

Whether you are feeling anxiety depression you can use tools to engage your social nervous system to re-establish higher order nervous system functions. For example, if you are experiencing anxiety you are likely in fight or flight, a key defense reaction of sympathetic nervous system. Sympathetic actions involve mobilization; the need to move your body to release the build of stress cortisols. You can engage your social nervous by rubbing your hands together vigorously and making physical contact to your own face, neck, upper chest, arms, and legs. You can also explore physical movements that feel safe and grounding such as going for a walk or shaking your arms and legs to release stress. When we feel safe we can engage our social nervous system to use the energy of the sympathetic nervous system to dance, play, and laugh. Feeling shut down, collapsed, depressed, or numb is an indication that you are in the defensive reactions of your parasympathetic nervous system which is characterized by immobilization. If you have a history of trauma it is possible that you are perceiving threats in your environment that are not actually occurring in the here and now. This is because a common symptom of PTSD is confusion between the past and the present. In this case, your social nervous system can help you find clues that help you recognize that you are not in imminent danger now which helps you access the positive, relaxing elements of your parasympathetic nervous system of “rest and digest.” When possible, turn towards a loving connection with a friend, caring partner, or a pet. If you are able, make eye contact or call someone you trust and listen to the sound of their voice. You can also visualize a loving animal, friend, or protective ally to restore a felt sense of connection. When we can embrace immobilization with safety we can access the nourishment of the relaxation response.

Implications for Healing PTSD

The polyvagal theory in action can allow you to increase your sense of freedom in body and mind when experiencing symptoms of anxiety, panic, or depression. Here are some suggestions: Focus on the present moment. Engage the sense of smell with an essential oil that brings a positive association or feeling. Re-establish connection by calling a friend, snuggling with your pet, or loving self touch. Express feelings through talking, writing, drawing, movement. Focus on your breath as a fine tuning mechanism to regulate the nervous system. Engage in a mindfulness practice such as meditation or therapeutic yoga. Allow yourself to play.

Trauma , The Nervous System & The Gut

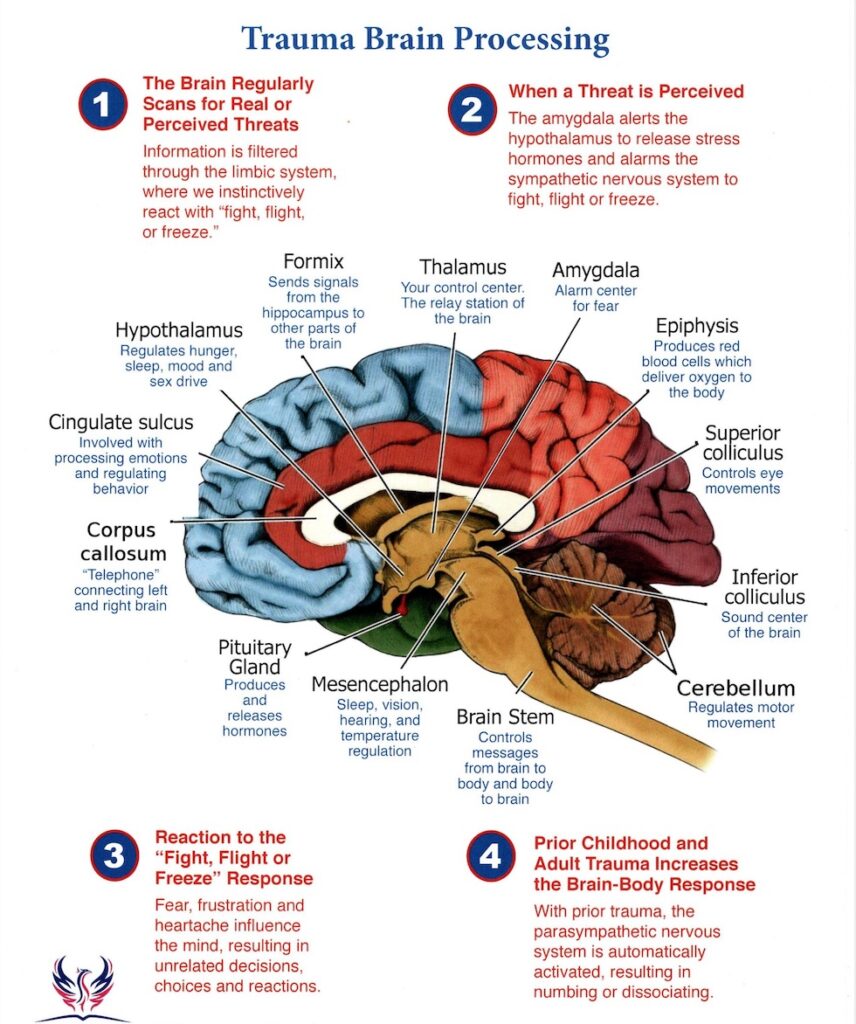

Effective treatment needs to involve (1) learning to tolerate feelings and sensations by increasing the capacity for interoception, (2) learning to modulate arousal, and (3) learning that after confrontation with physical helplessness it is essential to engage in taking effective action. Introception is the process of embodied mindfulness, and in neuroscientific terms it is becoming aware of visceral afferent information (bodily sensations). Being traumatized is continuing to organize your life as if the trauma was still going on unchanged and every new encounter or event is contaminated by the past. After trauma the world is experienced with a different nervous system, a survivor’s energy now becomes about suppressing inner chaos at the expense of spontaneous involvement in life. These attempts to maintain control of these unbearable physiological reactions can result in a whole a range of physical symptoms such as autoimmune diseases, this is why it is important in trauma treatment to engage the entire organism, body, mind and brain. Deactivation of the left hemisphere of the brain has a direct impact on the capacity to organize experience into logical sequences and to translate our shifting feelings and perceptions into words. Without sequencing we cannot identify cause and effect, grasp the long-term effects of our actions or create coherent plans for the future. When something reminds traumatized people of the past, their right brain reacts as if the trauma were happening in the present but because their left brain may not be working very well, they may not be aware that they are re-experiencing and reenacting the past, they are just furious, terrified, enraged, shamed or frozen. After the emotional storm passes, they may look for something or somebody to blame for it, for their behaviour, they may say,

“I acted this way because you looked at me like that or because you were late”. This is called being stuck in fight or flight.

In trauma recovery where the left hemisphere is activated through speaking of the traumatic past and making sense of what happened within a safe environment, the left brain can talk the right brain out of reacting by saying that was then and this is now. This can only happen when safety is establish through attunement with a therapist where the amygdala is down regulated, this can often take some time for traumatized people as the amygdala tends to stay in a heightened state of arousal ready for fight or flight even years after then traumatic event or experience. Even the slightest detection of a threat can cause extreme arousal of this system. Minor stimuli will illicit major responses. This is why it is important to engage the left and right-brain in trauma recovery, whilst body based interventions are absolutely imperative and ofcourse right brain to right brain affect reglation is critical for rewiring the nervous system contributing to long term character change and critical for trauma recovery, these interventions may be undermined should they exclude left-brain based activities. Body based interventions such as dance; massage and yoga are a fantastic adjunct to psychodynamic psychotherapy. Lazar’s study lends support to the notion that treatment of traumatic stress may need to include becoming mindful: that is, learning to become a careful observer of the ebb and flow of internal experience, and noticing whatever thoughts, feelings, body sensations, and impulses emerge. In order to deal with the past, it is helpful for traumatized people to learn to activate their capacity for introspection and develop a deep curiosity about their internal experience. This is necessary in order to identify their physical sensations and to translate their emotions and sensations into communicable language—understandable, most of all, to themselves. Traumatized individuals need to learn that it is safe to have feelings and sensations. If they learn to attend to inner experience they will become aware that bodily experience never remains static. Unlike at the moment of a trauma, when everything seems to freeze in time, physical sensations and emotions are in a constant state of flux. They need to learn to tell the difference between a sensation and an emotion (How do you know you are angry/afraid? Where do you feel that in your body? Do you notice any impulses in your body to move in some way right now?). Once they realize that their internal sensations continuously shift and change, particularly if they learn to develop a certain degree of control over their physiological states by breathing, and movement, they will viscerally discover that remembering the past does not inevitably result in overwhelming emotions. After having been traumatized people often lose the effective use of fight or flight defenses and respond to perceived threat with immobilization. Attention to inner experience can help them to reorient themselves to the present by learning to attend to non-traumatic stimuli. This can open them up to attending to new, non-traumatic experiences and learning from them, rather than reliving the past over and over again, without modification by subsequent information. Once they learn to reorient themselves to the present they can experiment with reactivating their lost capacities to physically defend and protect themselves.

Trauma can be conceptualized as stemming from a failure of the natural physiological activation and hormonal secretions to organize an effective response to threat. Rather than producing a successful fight or flight response the organism becomes immobilized. Probably the best animal model for this phenomenon is that of ‘inescapable shock,” in which creatures are tortured without being unable to do anything to affect the outcome of events. The resulting failure to fight or flight, that is, the physical immobilization (the freeze response), becomes a conditioned behavioral response. In his book, Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self, Allen Schore has outlined in exquisite detail the psychobiology of early childhood development involving maturation of orbitofrontal and limbic structures based on reciprocal experiences with the caregiver. Dysfunctional associations in this dyadic relationship result in permanent physicochemical and anatomical changes, which have implications for personality development as well as for a wide variety of clinical manifestations. An intimate relationship may exist, with negative child/care giver interaction leading to a state of persisting hypertonicity of the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems that may profoundly affect the arousal state of the developing child. Sustained hyperarousal in these children may markedly affect behavioral and characterological development. Many traumatized children and adults, confronted with chronically overwhelming emotions, lose their capacity to use emotions as guides for effective action. They often do not recognize what they are feeling and fail to mount an appropriate response. This phenomenon is called alexithymia, an inability to identify the meaning of physical sensations and muscle activation. Failure to recognize what is going on causes them to be out of touch with their needs, and, as a consequence, they are unable to take care of them. This inability to correctly identify sensations, emotions, and physical states often extends itself to having difficulty appreciating the emotional states and needs of those around them. Unable to gauge and modulate their own internal states they habitually collapse in the face of threat, or lash out in response to minor irritations. Dissociation and/or Futility become the hallmark of daily life.

Exposure to extreme threat, particularly early in life, combined with a lack of adequate caregiving responses significantly affect the long-term capacity of the human organism to modulate the response of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems in response to subsequent stress. The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is primarily geared to mobilization by preparing the body for action by increasing cardiac output, stimulating sweat glands, and by inhibiting the gastrointestinal tract. Since the SNS has long been associated with emotion, a great deal of work on the role of the SNS has been collected to identify autonomic “signatures” of specific affective states. Overall, increased adrenergic activity is found in about two-thirds of traumatized children and adults. The parasympathetic branch of the ANS not only influences HR independently of the sympathetic branch, but makes a greater contribution to HR, including resting HR. Vagal fibers originating in the brainstem affect emotional and behavioral responses to stress by inhibiting sympathetic influence to the sinoatrial node and promoting rapid decreases in metabolic output that enable almost instantaneous shifts in behavioral state. The parasympathetic system consists of two branches: the ventral vagal complex (VVC) and the dorsal vagal complex (DVC) systems. The DVC is primarily associated with digestive, taste, and hypoxic responses in mammals. The DVC contributes to pathophysiological conditions including the formation of ulcers via excess gastric secretion and colitis. In contrast, the VVC has the primary control of supradiaphragmatic visceral organs including the larynx, pharynx, bronchi, esophagus, and heart. The VVC inhibits the mobilization of the SNS, enabling rapid engagement and disengagement in the environment.

The Dorsal Vagal State and manifestation of autoimmune disorders

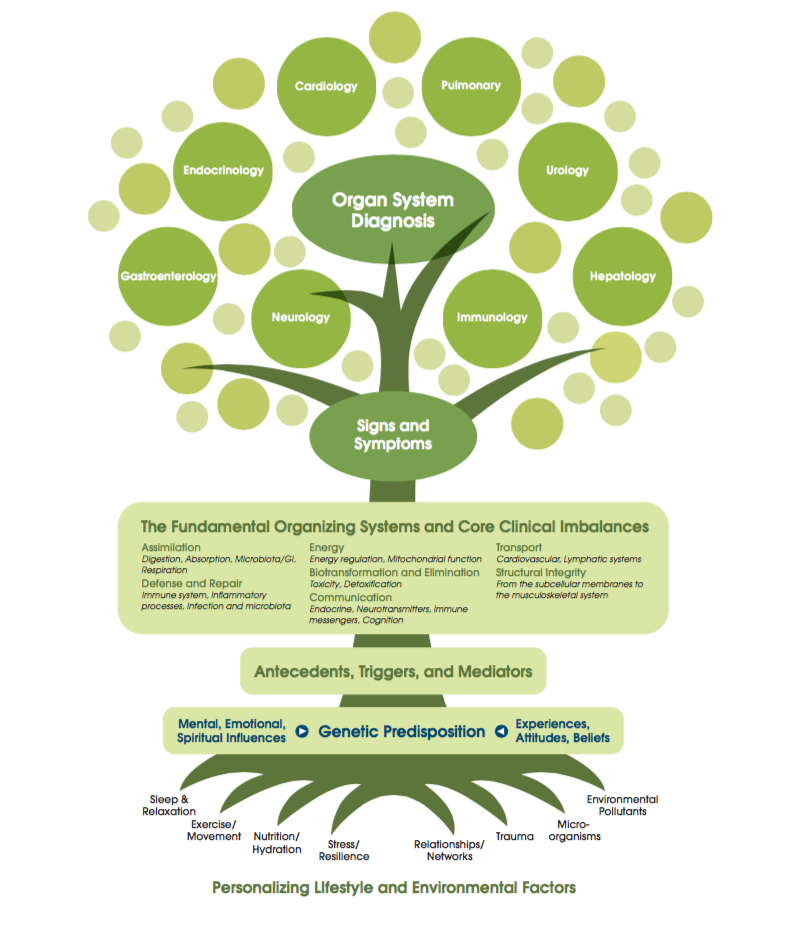

People who are in the dorsal vagal state a lot which is the state when the amygdala is activated due to a detection of a slight threat in the environment consciously or unconsciously through neuroception and the traumatized person goes into a state of learned helplessness or what is called dissociation or freeze response which is an unconscious conditioned fear response, the body’s reflex to an internal or external stimuli from a cue of an original trauma. This will activate all the viscera, your heart, your lungs, your colon, your stomach, all of these are run unconsciously by the dorsal vagal nucleus and if you have syndromes where you are in the freeze response a lot, the dorsal vagal nucleus will be hyperactive and you will get syndromes of hyperactivity within the viscera and that can be characterized by Irritable bowel disease, colitis and other autoimmune diseases.

These are cyclical diseases which means they oscillate between sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system meaning the symptoms come and go which is why the medical profession very often can not diagnose the problem or refer to it as psychosomatic meaning it is a condition of the mind when in fact it is actually emotionally driven physiological conditions of the gut and the brain. Problems with the gut are common with people who have had trauma, it is the physiology of trauma that drives these conditions and so if you heal the trauma you can heal the disease. These conditions are also referred to as neurosomatic, which means they are brain based conditions, physical conditions caused by abnormal function of the brain.

The Amygdala is the agent of fear conditioning, it stores emotionally based memory positive and negative, it is also the gate keeper for responding to threat by activating the fight or flight response, when the fight or flight response is not successful, such as you can not escape the traumatic event, the body goes into a freeze response. The freeze response is predicated by the effects of early childhood experiences, the freeze response is also called dissociation. When dissociation happens you are dysregulated, Dissociation is based a lot on what happened in childhood that allowed you to develop the brain in a way to prevent that from happening too easy. This has to do with Allan Schore’s work on attunement, the part of the brain that controls this regulation of autonomic nervous system and emotional system, which is the orbital frontal cortex. This develops in a healthy attuned infant and shrinks in a neglected infant. We need a developed orbital frontal cortex to regulate us over our lifetime and prevent us from going into freeze states and dysregulation. Helplessness is the essential ingredient for the freeze response. The freeze response is a motor action, which perpetuates the escape behaviour in a way that erases all the procedural (Implicit) memory of that trauma. If you have a threat and don’t discharge the freeze response, you are conditioned thereafter to any body cues related to that traumatic event.

The vagus nerve also detects inflammation or infection in the body and relays signals from the brain stem along its southbound fibers. This signal prompts other nerves to release norepinephrine, which makes immune T cells in the spleen release the chemical acetylcholine to depress inflammation via macrophages.

Conclusion

Interoceptive, body-oriented therapies can directly confront a core clinical issue in PTSD: traumatized individuals are prone to experience the present with physical sensations and emotions associated with the past. This, in turn, informs how they react to events in the present. For therapy to be effective it might be useful to focus on the patient’s physical self-experience and increase their self- awareness, rather than focusing exclusively on the meaning that people make of their experience—their narrative of the past. If past experience is embodied in current physiological states and action tendencies and the trauma is reenacted in breath, gestures, sensory perceptions, movement, emotion and thought, therapy may be most effective if it facilitates self-awareness and self-regulation. Once patients become aware of their sensations and action tendencies they can set about discovering new ways of orienting themselves to their surroundings and exploring novel ways of engaging with potential sources of mastery and pleasure.

Working with traumatized individuals entails several major obstacles. One is that, while human contact and attunement are cardinal elements of physiological self-regulation, interpersonal trauma often results in a fear of intimacy. The promise of closeness and attunement for many traumatized individuals automatically evokes implicit memories of hurt, betrayal, and abandonment. As a result, feeling seen and understood, which ordinarily helps people to feel a greater sense of calm and in control, may precipitate a reliving of the trauma in individuals who have been victimized in intimate relationships. This means that, as trust is established it is critical to help create a physical sense of control by working on the establishment of physical boundaries, exploring ways of regulating physiological arousal, in which using breath and body movement can be extremely useful, and focusing on regaining a physical sense of being able to defend and protect oneself. It is particularly useful to explore previous experiences of safety and competency and to activate memories of what it feels like to experience pleasure, enjoyment, focus, power, and effectiveness, before activating trauma-related sensations and emotions. Working with trauma is as much about remembering how one survived as it is about what is broken.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.